Our own, proudly our own

- Salvatore Laudicina Ramirez

- Jul 29, 2022

- 5 min read

The Colombian Pacific is the cradle of men and women who have written important chapters in different sectors of the country's contemporary history. For the Quibdó African Film Festival, they are a living legacy for new generations. An inheritance that allows us to affirm that the region is full of magical characters and stories. Protagonists of subjective films that do not need the big screen to shine and leave their mark.

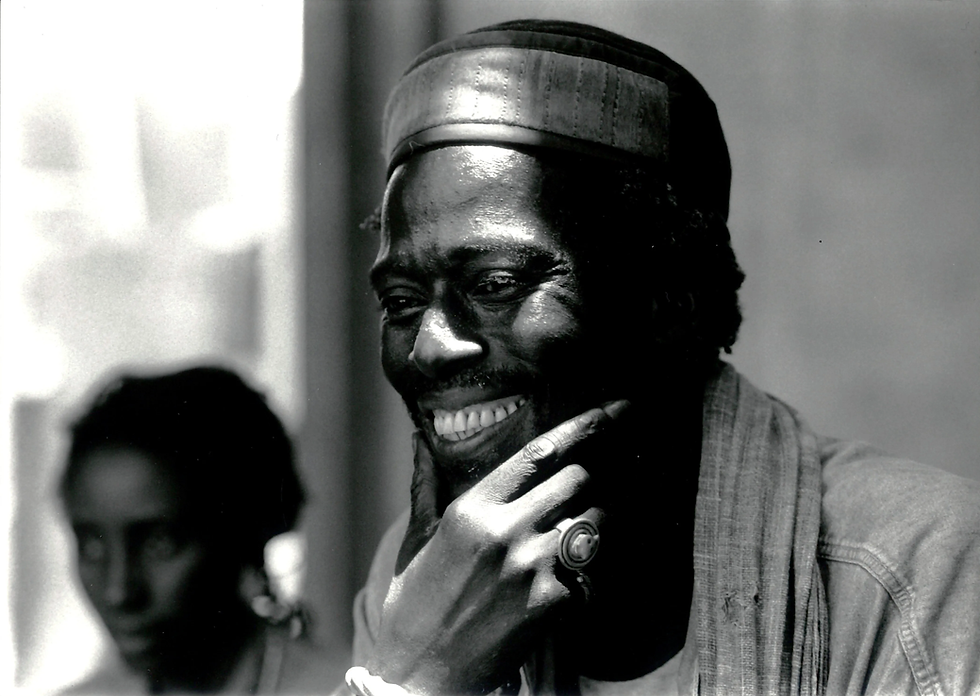

The Pacíficopreñez by José Éibar Castillo

Fertile and vigorous, demonstrating his gifts as a great lover, the brush sows his sperm of colors and shapes in the boiling genital of the virgin canvas. Libertarian orgasm, emancipated moans of Afro-descendants who pay tribute to their ancestors.

Abstracted from reality, submerged in the walls of the Mandinga workshop, located in Santiago de Cali, the erotic downpour penetrates the depths of José Éibar Castillo. In that tide of metaphorical spermatozoa, one of them manages to enter the creative ovum of the artist from Tumaco.

It smells like the pregnancy of a man of African descent. But Castillo's pregnancy is not just any pregnancy. It is a 'Pacíficopreñez' that makes the soul shake with the rhythm of a happiness born to honor the feelings of his ethnic group.

As Olga Yolanda Rojas expresses it, "the master Éibar Castillo is compiling the life of the Pacific. His pictorial work is playfulness in oil and acrylic colors. These large format paintings cross the viewer's path like the gaze of an old friend who demands time and attention. These works speak and steal the breath".

Each birth is a celebration where he pushes with fine strokes to bring to the world characters such as the midwife Mamanuncia, a tribute to the women who dedicate their lives to this noble profession.

For him, birth is to travel back in time, to return to childhood and dust off memories. It is obligatory to meet the mischievous and clever boy, unconditional friend of the sea, apprentice of Humberto Rosero, who teaches him how to make sheet metal.

That non-school year is perhaps one of the most pedagogical of his childish life. Although he does not sit at a desk or live in a classroom, the knowledge he gains turns his days into exciting adventures.

Educated with effort and sacrifice by his mother, a woman who earns her living as a laundress, he learns at an early age the value of work and the meaning of family solidarity.

Along with those responsibilities, which are useful for the determination of adult days, art palpitates timidly in his first drawings. Without fear of exaggeration, the dream of being an artist takes the form of a giraffe that must be accommodated in a small and friendly body.

Later, realizing that his friends were ahead of him, he enrolled in the Colegio Industrial and continued his elementary school studies. School years filled with mathematics, Spanish and masterly sketches on notebook pages.

In 1973, together with his mother and brother, he left the Pearl of the Pacific to unpack his hopes and desires in a modest house in Sucursal del Cielo. New life, new opportunities. Tumaco is the beloved land, but Cali opens the doors of progress.

A fleeting return to the present. José Éibar painstakingly polishes the features of a couple of ancestors who work in the fields. The priority is to turn the painting into a visual, political and vindicating discourse that accounts for the preponderant role of Afro-descendants in the social, economic and cultural development of the region.

Having said that, the biographical preterit peeks through one of the workshop's windows. It is necessary to diminish the contractions with memories.

City life brings favorable changes. With the help of his sister, who works in the house of the manager of an electrical cable company, Castillo gets a job. Simultaneously, he falls madly in love with a city where salsa, sports, culture and intellectuality walk freely in the streets and neighborhoods.

Between the songs of Héctor Lavoe and the boogaloo of Pete Rodríguez, the giraffe, his longed-for dream, is transformed into a fantastic animal, born to graphically relate the courage and greatness of an excluded people.

José Éibar intends to ride that animal, fly the Cali sky and put into practice the example of his mother and the teachings of Humberto Rosero. It is a debt to himself, to his family and to his ancestors.

He studied Plastic Arts at the Instituto Popular de Cultura (IPC), an academic journey that began in 1979 and culminated in 1984. From that moment on, Castillo is divided into two bodies: one that produces to survive in capitalist society and the other that produces to fully experience the delight of painting as a way of existing and recognizing himself as a black man, a citizen of a Colombia clothed in structural racism and discrimination.

It is fair to confess that his Pacíficopreñez finds a place and oxygen in the second body. Although he has always been clear about his vocation, the discovery of the African diaspora is an important milestone. Past, present and future meet to establish a dialogue with the spirits of the men and women of the family tree.

The polyphony of voices yields a transcendental conclusion: Colombia's Afro-descendants were denied the right to turn art into an echo of their struggles, an affront to the talent and thought of the ancestors brought to the American continent to be enslaved. The internal call shouts endlessly, fiery as fire and irresistible as his beloved sea in the hot days of Tumaco.

Since 2000, Castillo proudly exhibits the majesty of Africa as mother territory and invaluable ancestral legacy of those who today inhabit rivers, trails and estuaries. Among fertile brushstrokes, virgin canvases, libertarian orgasms and moans of ancestral emancipation, José Éibar Castillo has proudly given birth to Los hijos de la Mandinga (2012); Mi color poderoso (2016) and El cangrejo azul (2019). He has exhibited in different venues in the capital of Valle del Cauca (ICESI, Univalle, Centro Cultural de Cali) and galleries in the United States (Atlanta, Houston, New York, Miami and Orlando).

Possessed by ancestral spirits, the second body pushes with fine strokes to give the final touches to the portrait. At times, the person holding the brush is a brave slave who turns the walls of the Mandinga workshop into his revolutionary fortress after escaping from his master. At other times, it is an aging black woman who contemplates painting to find herself.

The priority is to turn childbirth into a journey of multiple faces that deconstruct the ego, to attend to a deep reading of those who can re-exist and be heard.

Fertile and vigorous, demonstrating its gifts as a great lover, the brush sows its sperm of colors and shapes in the genital bulging of the canvas. Libertarian orgasm, emancipated moans of Afro-descendants who pay tribute to their ancestors.

It smells like the pregnancy of a man of African descent, because the men of the Pacific also have the right to give birth, metaphorically speaking, to celebrate a legacy that makes them unique.

In Tumaco, until the end of time, the experiences of this man pregnant with art and resistance must be narrated orally. Those who listen to them are free to believe or not to believe.

Whether the natives believe them or not, the sea, the ancestors and life will always praise the Pacíficopreñez by José Éibar Castillo.

Comments