The saturation of black: aesthetics of fullness

- QAFF Fundation

- 4 days ago

- 5 min read

For a long time, cinema had to admit something shameful: it didn't know how to look at Black skin. Official history has relegated this observation to the realm of technical problems, gamma curves, and capricious emulsions, but the way lighting is configured always reveals something about how we hierarchize bodies.

The technique, or how to illuminate certain faces

For nearly a century, Kodak regulated the general perception of color. In their laboratories, they worked with "Shirley cards"—test cards depicting white women with flawless smiles, fair skin, and flattering lighting. The principle was simple: everything had to be adjusted until Shirley looked "right."

The consequences, however, were less obvious. Black skin appeared too dark or burned, its contours absorbed by shadow, its nuances dissolved. On screen, black became an indistinct mass, a blurred presence suggested rather than seen. What was presented as a technical bias silently perpetuated the colonial logic: black as a defect, as a lack of data.

Bradford Young, a cinematographer, decided to approach this "problem" as his starting point. In Pariah (2011), Middle of Nowhere (2012), and Selma (2014), he developed a luminous visual language that rejects the standard white as an invisible reference point. Soft lighting, multiple angles, meticulous post-production work: suddenly, black skin reveals an infinite range, from dense brown to bluish-black, from warm copper to deep purple. The question ceases to be "how to avoid loss of detail?" and becomes "what nuances compose this presence?"

Young reminds us that technique is never neutral. Filming Black people is not an optical puzzle, but a political decision: deciding that these bodies deserve precision, sophistication, and respect, and finding the tools to fulfill that promise.

Kerry James Marshall: Black, Excessively

Let's leave the room in darkness for a moment and go to a museum. You are looking at a painting by Kerry James Marshall. The figures staring at you are black, not brown, not "chocolate," but so black that the pigment seems to absorb the light instead of reflecting it.

Marshall works in layers, darkening the already black even further, thickening the surface to create a depth that no longer obeys the rules of realism. His figures do not seek to resemble a specific model. They approach a kind of Platonic ideal of black, an essence that rejects all dilution, all chromatic concessions.

This gesture is not merely a stylistic effect. It forces the viewer's gaze to readjust. Faced with these saturated faces, the eye, accustomed to a certain transparency, can no longer passively consume the image. It requires time, attention, and concentrated effort to discern the contours, the details, the minute variations in this hyperbolic black. Marshall thus inverts the power dynamic: it is no longer the black subject that must be lightened to become legible, but the viewer who must accept a shift in perspective.

In his paintings, black is not a void in color. It is a fullness that overflows, that saturates, that actively resists the gaze shaped by centuries of colonial images.

Touki Bouki : Opacity as a right

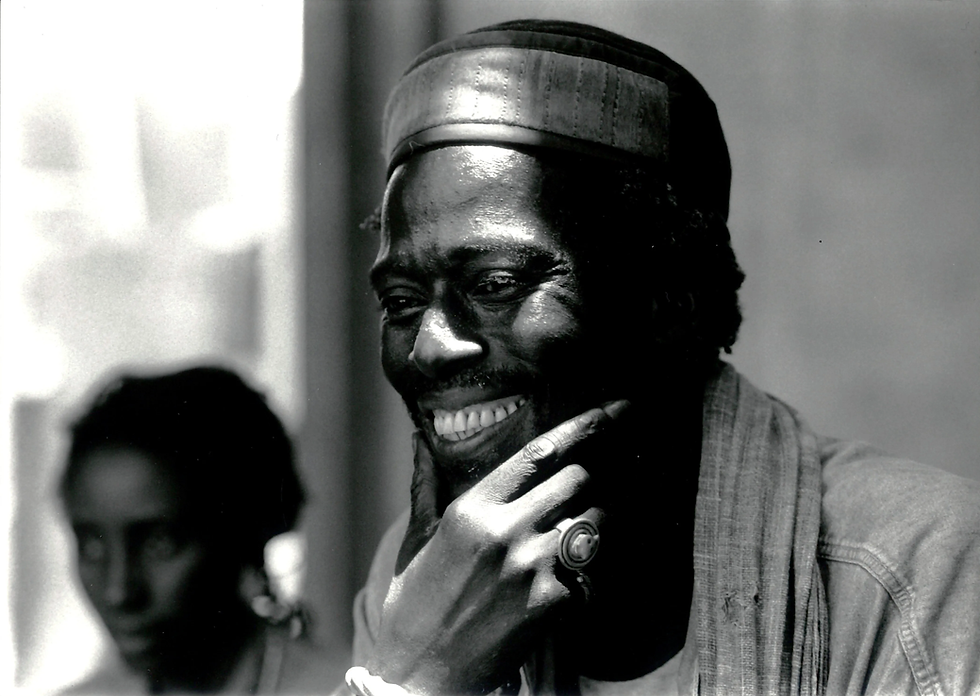

1973, Dakar: Djibril Diop Mambéty directs Touki Bouki , a film that will become both a myth and a source of unease. What's disturbing is not only what is shown, but the way the film refuses to be completely transparent.

The editing seems to play with narrative expectations. Waves crash against rocks amidst urban scenes, animals cross the frame without apparent justification, time distorts, jumps, and repeats itself. The characters speak in images, in metaphors that the film never bothers to culturally subtitle. We can follow the story, certainly, but something constantly eludes us, as if part of the narrative were unfolding in a language not everyone understands.

Mambéty puts into practice, image after image, the concept of opacity so dear to Édouard Glissant. The Martinican philosopher asserted that colonized peoples had a right to opacity, the right not to be completely legible, completely accessible to the gaze of the other. Touki Bouki embodies this right: the film offers no keys to interpretation for the foreign viewer, it does not soften its symbols or explain its rituals. Some will understand it immediately, others slowly, and still others will never fully grasp it.

Here, "I don't understand everything" is not a mistake to be corrected, but a condition of existence. Opacity is an aesthetic choice, but also a political statement.

Darkness as a refuge

Darkness, in the history of Black people, is not just a backdrop. It protects, conceals, and offers respite. It was at night that forbidden meetings took place, rituals outlawed by the colonizer were performed, dances of resistance were held, and ceremonies were held where people reconnected with spirits that the official order preferred to silence.

Marronage, the practice of slaves escaping from plantations to build communities in forests, mountains, and scrublands, depended on a precise understanding of shadows. Darkness became a strategic ally, an unprotected space, a blind spot in the panoptic gaze. Night offered a form of relative freedom, a moment when one could find oneself away from the watchful eye of the master.

African cinema has not forgotten this history. Night scenes abound, and they don't just serve to create atmosphere. They suggest that real life, the one not presented to an external audience, unfolds in the shadows. For Fred Moten, the African American theorist, this idea materializes in a "Black life" that thrives precisely in what escapes surveillance: nighttime gatherings, clandestine clubs, hushed conversations in a dimly lit corner of a bar. This world pulsates, invisible yet intensely alive.

From limited shadow to chosen light

Between the saturated blacks of Kerry James Marshall, the overflowing darkness of Touki Bouki , and the patient illumination of Bradford Young, a constellation of aesthetics emerges, all rejecting the dominant definition of black as lack. They consider saturation, opacity, and night not as problems to be solved, but as resources.

These gestures are not merely stylistic. They transform what we know: they affirm that black is not an anomaly in a system calibrated for white, but a legitimate starting point for rethinking that system. Being black within a visual apparatus designed to erase you becomes, in these hands, an opportunity to create other rules, other images, other narratives.

In the next installment of this series, “NOIR: From Imposed Shadow to Chosen Light,” developed within the framework of the Quibdó African Film Festival, the focus will shift to the future. It will explore Afrofuturism, Sun Ra’s claim to Saturn as the official direction, Pumzi ’s vision of Africa thirty-five years from now, and how these Black futures are already being written, frame by frame.

Comments