Chosen Darkness: Toward Other Ways of Knowing

- QAFF Fundation

- 8 hours ago

- 5 min read

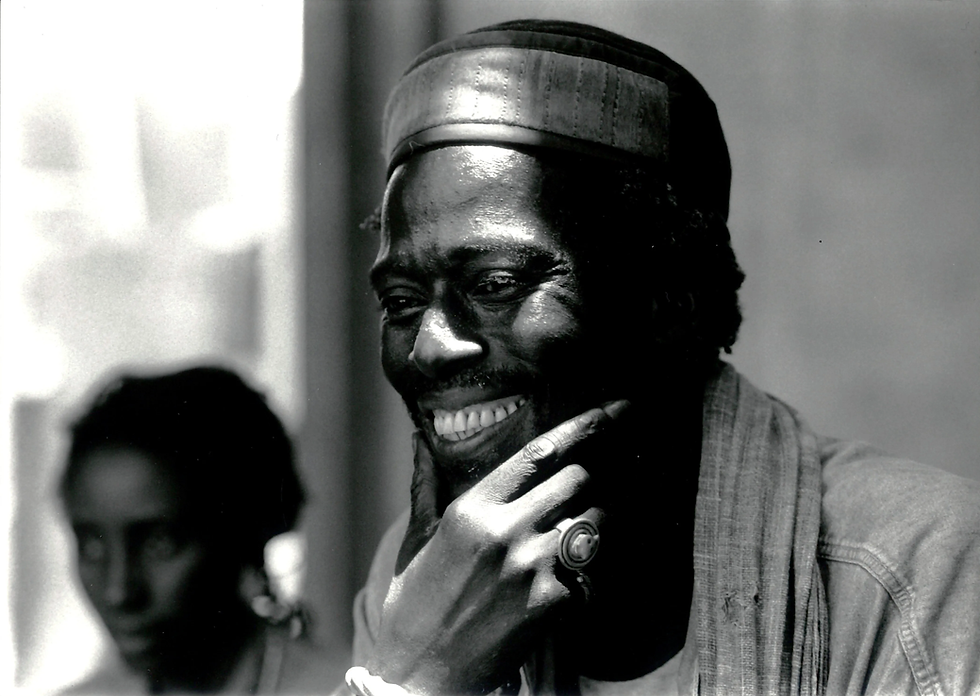

Six texts later, the journey begins to take shape. We have followed blackness from African cosmogonies, where it was plenitude, to the projection rooms where colonialism reduced it to an absence, before watching the camera pass into other hands from Sembène to Wanuri Kahiu, from Kerry James Marshall to Sun Ra, from the Atlantic-as-cemetery to the Atlantic-as-corridor. One question remains, the vastest and the most discreet: if we change how we film and paint blackness, do we not end up shifting what we call knowing?

Knowledge, Always Somewhere

Western universalism likes to present itself as a viewpoint that is none: neutral, objective, valid everywhere, a panoramic view from nowhere. But behind this elevated tone hides a simpler operation: a local perspective that of Western Europe elevated to the status of reference norm. The great dichotomies structuring this thought reason against emotion, mind against body, culture against nature, civilization against savagery are not natural certainties; they served, very concretely, to hierarchize human beings. Reason, mind, culture, civilization on one side; emotion, body, nature, savagery on the other.

African epistemologies, by contrast, start elsewhere. Ubuntu "I am because we are" refuses the self-sufficient individual, isolated from his bonds. Sankofa, that Akan bird that moves forward while looking backward, establishes as a principle that the future is built in dialogue with ancestors and the traces they left behind. Édouard Glissant, with his "thinking of the trace," claims the right to fragmentation, to non-linear narratives, rather than to a forced coherence supposed to explain everything. These ways of thinking do not come to "complete" Western universalism: they reveal that it too is situated, that it speaks from a precise place, at a precise time. There is no gaze from nowhere.

Opacity, or the Right Not to Tell Everything

Glissant formulated a sentence that recurs like a refrain in this debate: "I claim for all the right to opacity." This is not merely a poetic flourish; it is a bomb beneath five centuries of colonial science. Colonialism was indeed accompanied by a demand for total transparency: to see everything, measure everything, classify everything. Anthropology carved cultures into categories, ethnography transformed knowledge into data, photography aligned bodies in "documentary series." To be colonized was also to be rendered entirely legible to the other's gaze.

Yet whoever sees without being seen holds power. Transparency, in this context, is not moral virtue but a technique of control. Glissant inverts the gesture: he makes opacity a form of resistance. The right not to be fully understood. The right to keep secrets, zones of silence, mysteries that will never be fully translated to the outside.

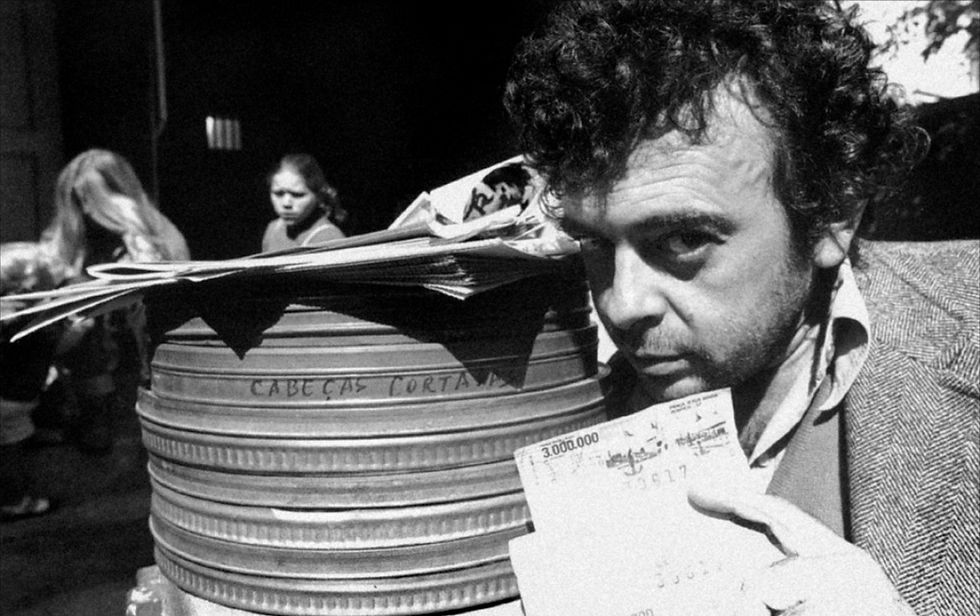

This opacity has nothing to do with obscurantism. It simply acknowledges that certain knowledge cannot be possessed as one possesses a file, but can only be approached through relation, immersion, participation. One does not "understand" a cosmology by skimming through an ethnology book; one enters it by participating in rituals, by living with those who carry it, by accepting that not everything will ever be available. When a film like Touki Bouki refuses to explain its symbols to the foreign viewer, it puts this principle into practice: part of the meaning remains opaque, and this is no flaw.

Black Epistemologies as a Toolbox

At a time when ecological crisis, digital saturation, and widespread fatigue with Western grand narratives are accumulating, these Black epistemologies increasingly resemble a toolbox. On ecology, first: cosmologies that refuse to radically separate humans from non-humans propose other ways of inhabiting the Earth. If a river is an ancestor, if a forest is a community, if an animal is a relative, environmental destruction ceases to be mere "collateral damage" and becomes an act of ontological rupture.

On technology, communal traditions offer a counterpoint to the atomization induced by certain digital devices. Tontines collective savings systems show that it is possible to conceive financial networks founded on trust, reciprocity, and circulation, rather than pure extraction.

On knowledge itself, the plurality of modes of knowing through the dancing body, through ritual, through dream, through divination contests the monopoly of instrumental reason. These practices are not "pre-scientific": they are scientific in another way, attentive to dimensions of the real that measurement and calculation cannot capture.

Darkness as Methodological Choice

We have returned to our starting point, but with a slight shift. Darkness, which was imposed as a space of relegation, can become a space one chooses. Blackness, which was stigmatized as lack, can be cultivated as plenitude, as saturation, as refuge.

Transposed to the domain of knowledge, this idea has precise implications. Rather than wanting to illuminate everything with a violent light, the aim would be to preserve zones of shadow, spaces where curiosity coexists with respect. Rather than seeking to explain everything, accepting that certain mysteries persist not out of laziness, but on principle. Rather than demanding the other's transparency, recognizing their right to opacity as a minimal condition of relation.

Chosen darkness is not ignorance. It is a wisdom that knows one cannot know everything, and that certain knowledge is earned slowly, in patience and proximity, rather than through rapid extraction. One might say that viable future forms of thought resemble a darkroom more than a television studio: a place where images develop gradually, in time, rather than under permanent illumination.

The Journey Does Not End, It Changes Hands

Arriving at the sixth article, one might be tempted to conclude, to draw a clear line: from imposed shadow to chosen light, from human zoos to the Quibdó Africa Film Festival, from blackness as defect to Black skin filmed with the precision of a Bradford Young. But this kind of reassuring conclusion would be a jump cut from the subject. The movement is neither linear nor definitive.

Each generation, each filmmaker, each viewer must redo the journey: decide how they want to be seen, how they want to see themselves, what images they wish to produce and what knowledge they deem worth pursuing. African cinema, in this framework, is not only an artistic field; it functions as an epistemological laboratory, a place where other ways of looking, telling, and connecting are being tested.

This series closes on the page, but not in the theaters or on the squares of Quibdó, Ouagadougou, Durban, or Rio. Every screening, every post-film debate, every young person who discovers in the open air a story filmed on the other side of the Atlantic and thinks 'I could film my own' extends the movement. Blackness is not a void to be filled. It is a reservoir of possibilities, a density waiting to be recognized, celebrated, cultivated. Darkness is not what we flee to enter the light; it is, perhaps, the place where the forms of light we will need are being invented.

Comments